AI and the Consumption of Ghibli without Context

The Taiwanese town of Jiufen, a hot-spring resort situated on what once was a mining village. In busy tourist seasons, people most often go to take photos, purchase snacks and relive scenes that resemble Studio Ghibli's Spirited Away. It's an idyllic and colorful place that could have been storyboarded by the famed studio's animators. Photos of it were most likely fed into the machines of ChatGPT, Midjourney and other AI image generators to regurgitate "Ghibli-inspired" art, graphics and visual assets.

In the age of AI, Ghibli is a popular source for plagiarized, remixed and otherwise bastardized "artworks." Sam Altman, head of OpenAI, has bragged about "Ghibli memes" sweeping the internet, calling them a "net win for society." Plenty of people have pushed against the dissemination of these low-effort images. Simply put, people who can't make art by themselves or bother to pay an artist don't deserve praise for stealing art through AI generated content.

I actually want to take a step back from the shameless profiteering by AI corporations for a second, however, and contextualize it in the broader scope of how Studio Ghibli films are consumed.

OpenAI's usage isn't authorized, but what Studio Ghibli has licensed out continues to fascinated me. By and large, it isn't the difficult parts of their films that sell the best. People want to buy fluffy plush toys of Totoro, but don't want to think about the girls' chronically ill mother and their isolation and frustrations. No-Face also featured in merchandising, but not many people think of their failed attempts to eat away loneliness and rejection from other spirits.

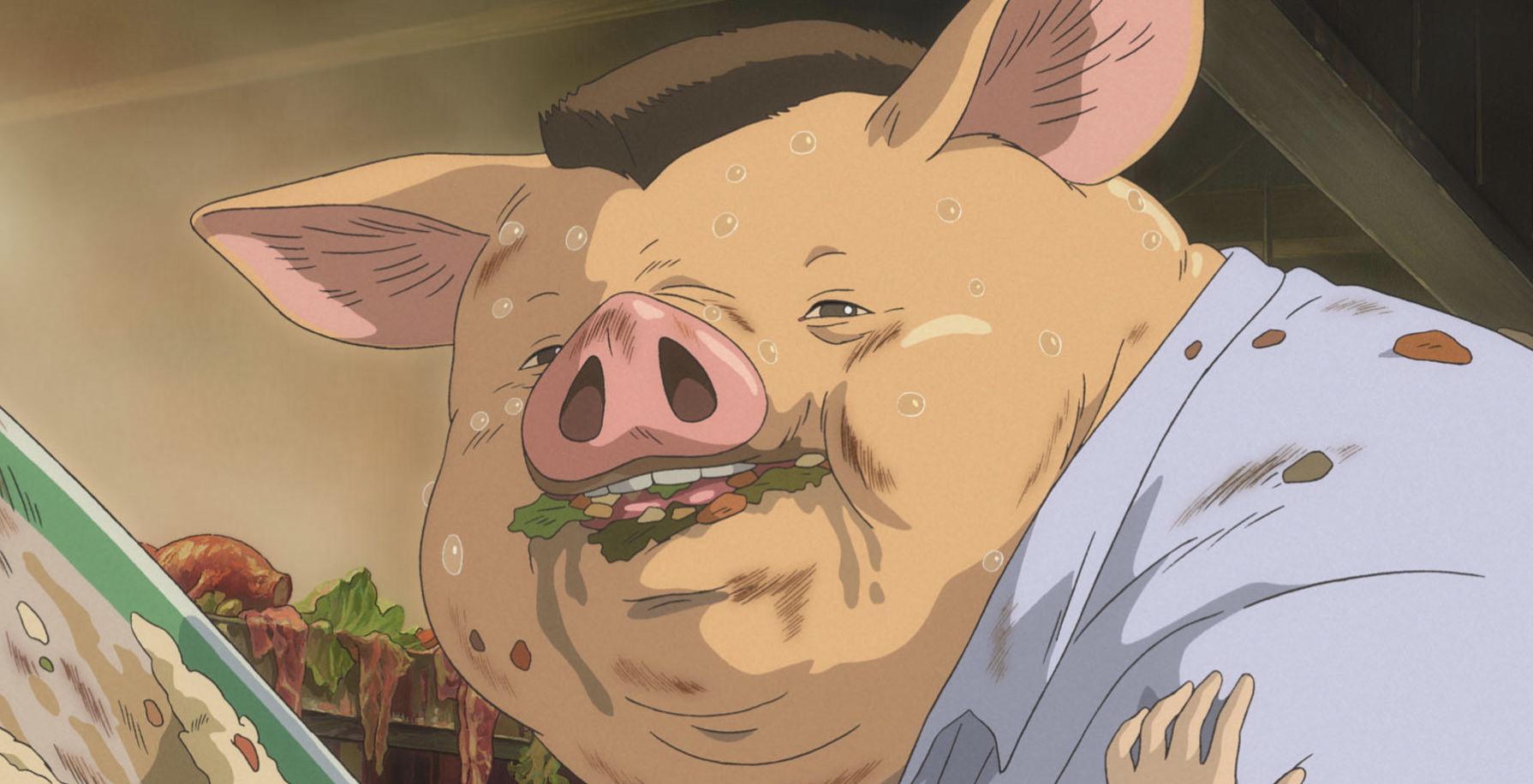

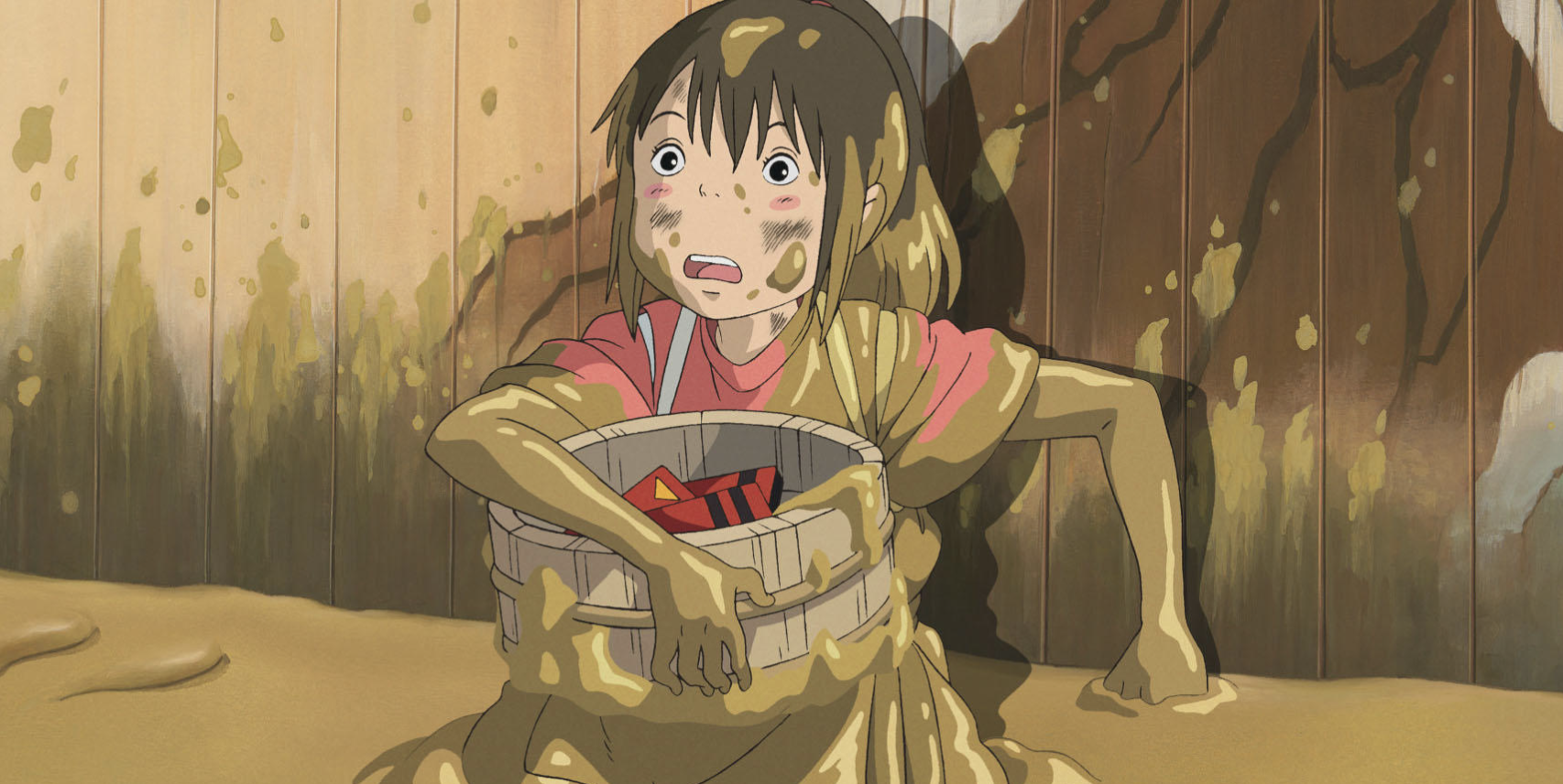

These storytelling details are wrinkles that are ironed out when they take the form of mascots who serve the primary purpose of simple, unobstructive representation of warmth and comfort. Merchandising doesn't include these visceral elements because they aren't profitable. Who exactly wants a plush toy of a battered Haku, bleeding and unconscious, as he's pulled from the sky by papercuts? Who's looking for Chihiro pulling out a bicycle lodged into a bath client from a veritable river of mud and pollution?

While it's understandable that people don't display these aspects of their favorite Ghibli movies, the visceral components of the movies are what make them living stories as opposed to the dead-eyed, glassy-expression AI images generated. You can understand the expressions that Sen has– her determination, her fear, her disgust– as clear as day. The physicality of her wrestling medicine down the throat of her dragon friend is instantly recognizable as he snarls, thrashes and roars in pain. This tactile demonstration of beauty and ugliness is present in many of the studio's other films as well, including the bird-poop ridden latest entry: The Boy and the Heron. That story is bloody as well, with its young hero spending most of the movie with a bandage over his head after he bashes himself with a rock until he bleeds to the point of unconsciousness.

When consumers decontextualize and erase these aspects of Ghibli movies and cherrypick scenery they like, they really do themselves a disservice. The bathhouse of spirits resembling the vacation resort of Jiufen is beautiful externally, but we realize soon that it is rife with ugliness in service of Yubaba's greed. Her staff cower before her as she counts her gold in her tower, sending razor-sharp paper people after anyone sowing discontent or treason. The worlds of Princess Mononoke, Nausicaa and Howl's Moving Castle, three other films with beautiful aesthetics, are similarly teeming with ugly, convulsing masses of violence and warfare. You won't see of this in what people choose to buy, sell, create or wholesale rip and plug into AI generators.

At the end of the day, I think we have a worthy question to consider here: what compels people to seek out merchandising, experiences and content that comforts them and allows them to consume without context? It's true that a lot of consumers crave escapism and want to find beauty in their artworks. With Ghibli, however, you see the extra steps taken to erase out the parts of the story, visuals and themes of the films that aren't considered pretty enough. The mud, blood, vomit, tears and bird shit simply isn't in the picture.

Perhaps it's this intuitive want for mind-numbing comfort that caused people to first buy Totoro plush toys and Howl's Moving Castle landscapes first, and then lead them to generate their own "Ghibli style" images. The relentless pursuit of consumption just continues, one product after another. It's fine, people say, if they have the money to spend on the habit. They can just pay for what they deem fair, and move onto the next visual treat.

I've seen that consumption before in the movies. It didn't end well.